It’s the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic and you’ve just been admitted to hospital. A flurry of personnel in scrubs and personal protective equipment (PPE) flocks in and out of your room. They are a blur of masks, face shields and gowns. Some introduce themselves, but you can’t process what they’re saying. You try to catch a glimpse of their badges to discern the face, name and profession, but the tiny, faded letters and pictures escape your sight. However, one person stands out in your mind: a nurse who struggles to insert an intravenous (IV) line. You’re a bit surprised, but you chalk it up to an off day, inexperience or that you have difficult veins. Months later, you’ve returned home and are back to 95 per cent of your full health when you receive a call informing you that you’ve been treated by an imposter nurse during your recent admission. Your mind begins to race as you consider what could have and did happen: how the nurse that struggled to place your IV left your arm marked with bruises

That scenario is inspired by real life examples of medical impersonation that have occurred throughout Canada and around the world (see Table 1). While there are countless instances where faux practitioners established their own independent physical and/or online practice, such as when a Toronto resident advertised themselves as a cosmetic surgeon, this article will focus on impersonation in recognized institutions like hospitals and clinics. The situation outlined above raises three questions:

1) What is the prevalence of medical impersonation?

2) What are the elements (factors and consequences) that allow medical impersonation to happen in the first place?

3) What are the potential solutions to deter and make medical impersonation more difficult?”.

Though impersonations seem to be relatively rare, there does not appear to be any formal statistic on its rate beyond the unregistered practitioners lists that provincially recognized professional associations such as the College of Physician and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) publish. Even then, these lists contain limited details regarding the circumstances; the most comprehensive sources of information we could find were largely from news agencies with inconsistent levels of detail.

People have the power to verify the status and registration of health-care teams through each professional order, such as searching for your nurse through Québec’s Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec (OIIQ). As you can imagine, this would be a cumbersome process as patients receive visits from as many as 18 different hospital personnel per hour; even in cases where patients are suspicious of select individuals, these databases are likely not common public knowledge. There is the added complexity of provincial differences in protected titles within health care and the variety of medical professions that have nuanced, unclear and/or contested scopes of practice. For example: in the realm of sports, exercise and rehabilitation, “kinesiologist” is protected in Ontario but not in Québec and most would have difficulty clearly defining and differentiating the following:

- Occupational therapist

- Personal trainer

- Kinesiologist

- Physiotherapist

- Athletic/sports therapist

- .Among physicians: Sports medicine; Physical medicine and rehabilitation (PMR); Orthopedic surgeon

Health-care systems rely on a level of inherent trust from the public, and health-care impersonation (among many other factors such as previous negative personal or historical experiences with the medical system, etc.) erodes this trust and renders health-care delivery more difficult. In addition, this diverts precious resources (salary, funding, opportunities, etc.) away from certified and qualified professional colleagues.

Among the 16 cases in Canada and internationally mentioned in our research, the most common factors in impersonations were:

- Stolen identity, accessed original or forged documentation/materials: Individuals were able to acquire certificates and registration information that were falsely created by themselves or diploma mills (where an estimated half of new United States PhDs are fake) or received original documentation from official certifying and regulatory bodies.

- Incomplete training and/or training in another health-care profession: Having previous experience in the field helps impersonators limit obvious medical errors.

- Impersonation at multiple institutions and/or impersonation after being caught: Oftentimes, individuals are caught and continue to work in either the same location or in other institutions.

- Improper verification of CV/documentation: During recruitment and onboarding, administration and staff fail to identify irregularities and/or verify the validity of an impersonator’s dossier.

- Psychiatric and/or intellectual disability:y: Individuals can be declared unfit to stand trial and have their cases dismissed due to their mental state.

- Clothing: white lab coat, stethoscope, etc.: The appearance of a health-care worker is easy to simulate and the inherent trust that patients and staff have make it easy for impersonators to blend in.

- Online impersonation: Social media, etc.

- Staff shortages: The need for health-care workers both before (a 2010 study found that Canadian hospital nurse turnover rate was at 19.9 per cent) and exacerbated by the pandemic puts undue pressure on staff to quickly review applicant portfolios and fill gaps in care. It encourages impersonators to fill this gap for prestige, monetary gain or due to a sense of personal duty to help the public in a time of crisis. The president of the Canadian Union of Public Employees Local 204, Debbie Boissonneault, has stated “[Hospitals] should be having regular staff. They shouldn’t have these uncertified [workers] coming from all over. They really need to beef up their staff so this doesn’t happen.”

- Whistleblower(s) fears: Potential reprisal and cultural, organizational and individual health-care factors prevent health-care workers from identifying both suspected imposters and/or malpractice. They may feel like they are “working against the team” and will cover for them instead.

Among the consequences in the 16 cases we examined, were fines, jail time, loss of employment, etc. (in 2019, Australia doubled the fines and added the possibility of three years prison time for impersonators of registered health practitioners); implementation of security practices, re-reviewing employee files, changing governing policies and protocols, etc.; and claim(s) of patient harm.

One of the simplest solutions for health-care organizations is to redesign employee ID badges. Health-care already places great importance on identifying patients and families, for the sake of greater communication, therapeutic relationship development, and delivery of high-quality care, so why not the same for health-care professions? Patients wish to know the roles of members of their health-care team and 88 per cent of patients say it is very important to know the training level of their emergency department doctor (medical student vs. resident vs. attending doctor). These are a crucial element of security that are often overlooked and that can also be repurposed at an institutional level to improve patient care and staff satisfaction and efficiency.

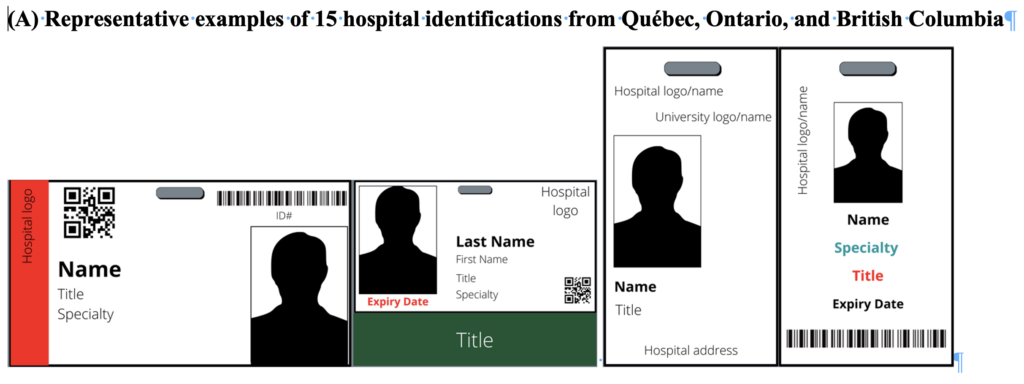

We explored health-care ID card designs of 15 sample IDs from various hospitals across three provinces in Canada (Fig. 1) and found some elements that should be standardized across the country:

- Photo: This should focus on the face and limit non-crucial identifying elements (a person’s shoulders/chest). A sleeve or overlaminate should be considered to protect the integrity of the photo from cleaning (for infection control) and/or friction. This overlaminate can use holographic pattern or other security features to deter fraud. Allowing for easy visual identification from a distance will also allow for all institutional IDs to be used as a portrait on PPE. Laminated headshot portraits fixed to the outside of a health-care worker’s PPE humanize the alienating appearance of masks. Based on feedback from the use of more than 3,700 PPE portraits through PPE Portraits Canada, having the hospital ID badge become the de facto PPE Portrait has the advantage of reducing the self-consciousness of health-care workers and allows for PPE portraits to be commonplace during both pandemic and non-pandemic times.

- Orientation: A vertical badge orientation is optimal for a larger image of the health-care professional while maintaining the essential elements of a hospital ID card.

- Badge buddy: This is an additional identifier that hangs below the ID badge and is solely dedicated to the person’s title and/or position, with easy identification through colour-coding. These decrease misidentification of health-care professionals’ positions and roles as well as workplace biases and stereotypes, leading to greater inclusivity. For example, female emergency physicians are at an increased risk of feeling undervalued when having to specify their role and female residents are more likely to be misidentified – a badge buddy reduces gender-based aggressions. These badges can educate patients regarding the range of professions within their interdisciplinary care, allowing for greater recognition and appreciation toward all health-care workers. In a similar vein, a pilot study looked at displaying the health-care professional’s name and role on scrub caps/headwear in the operating room (OR). This inexpensive intervention was found to improve teamwork and communication within the OR; badge buddies likely would have similar benefits in other environments and situations where teams aren’t as familiar with one another (such as with rotating trainees) and/or whenever PPE is used.

- Font size, colour, and bolding: This allows for contrast and emphasis on the most important information on the card. In some cases, the person’s last name would be bolded and/or larger than the first name and titles would be in a different color or be highlighted. Institutions should consider selecting a colour palette that accommodates for colour blindness.

- Expiration date: This is an important detail for temporary workers and trainees that rotate frequently.

- Multilingual: Necessary for greater local inclusivity.

- Humanizing touches: One of the hospital IDs had a heart printed onto it, indicating an institutional philosophy (likely care being given from the heart). Though non-empirical in nature, one doctor felt that “Hello my name is” badges helped humanize colleagues in the emergency department, an environment where staff are often unfamiliar with each other and short on time and resources.

- Removal of other element of unknown utility: hospital addresses; QR/bar codes; including both the hospital name and logo in addition to the affiliated-university’s name and logo.

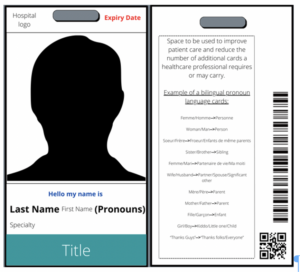

Fig. 1B shows additional elements that we would include in our ideal hospital identification:

- Pronouns: Gender-inclusive pronouns placed next to a health-care worker’s name. In addition to helping health-care professionals themselves, this can also help gender diverse patients and is a step forward to inclusivity. One example is Indiana university school of medicine offering pronoun badges.

- Back of ID: This is often left blank but can be used for:

- Important hospital codes and/or telephone numbers.

- Fire safety RACE/PASS (Rescue/Alarm/Contain/Extinguish & Pull/Aim/Squeeze/Sweep) that summarize the steps to take if a fire is discovered and how to operate a fire extinguisher.

- Information that may be part of an institutional campaign to enact practice/methodology change or that may be unit-specific such as McGill’s “True Colours” campaign distributed lanyards designed with the rainbow flag and pronoun language cards or a suicide warning signs card based on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale that assesses suicide risk.

- Streamlining through programmable IDs: Oftentimes, HCWs require various badges or cards to access different areas or services. Having a programmable ID badge that carries multiple functions is not only more ideal but can help significantly lower the carbon footprint of ID badges with an estimated savings of 50g of CO2 per ID card. Other benefits of single-sign on (SSO) badges include a cost-savings of more than $92,000 per hospital per year due to time saved by physicians and nurses; real-time location services to allow institutions to locate staff quickly and efficiently and limit delays in patient care; and a time savings for staff when a card combines parking, scrub, cafeteria, etc services.

One concern would be that if a card is lost and/or stolen, it would potentially give someone unfettered access. A robust, quick, and non-judgemental method of reporting, de-activating, and replacing a missing ID must be put in place. Moreover, in order to reduce costs to implement these changes, hospitals in a region should consider collaborating with one another to achieve volume discounts.

Though simple in concept and logistically complicated, redesigning health-care IDs can be one of many small steps to improve a systemic issue in health care while potentially saving costs.

The authors are executive members of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Portraits Canada (PPC), a student and volunteer-based organization that provides smiling headshot portraits to humanize health-care settings.

Table 1: Medical impersonations example cases in established health-care institutions.

|

Case number: Country(ies) Location(s) Dates (DD/MM/YYYY) and/or duration |

Role

Patient contact Harm |

Consequences for the impersonator

Security measures implemented |

| Case #1: Canada

Lakeshore General Hospital, Montreal 01/06/2021 1 day |

– Identified as a medical resident.

– Attempted 2 radiology requests but was quickly discovered. |

– No charges laid.

– Individual was placed in psychiatric care. – Hospital intensified their checks and verifications of medical staff. |

| Case #2: Canada

Several medical facilities, Montreal and Laval 21/11/2019-27/06/2021 7 incidents, 1.5 years |

– Claimed to be a general medicine resident and manager in medical clinics.

– Acquired 2 internships by appearing with a white lab coat and stethoscope and claimed to be a doctor on LinkedIn and Facebook. – Carried out consultations, but never carried out direct patient care. |

– The Quebec College of Physicians sought compensation for 9 counts and $67,500 and reported them on Facebook and LinkedIn.

– No criminal charges laid. |

| Case #3: Canada

St. Boniface Hospital, Winnipeg 02-17/07/2021 8 shifts, 15 days. |

– Despite not completing his training, he called the staffing office at the hospital saying he was a newly hired health-care aide and was scheduled for a shift.

– After the first shift, the error was discovered, but continued to work thereafter. – Did not have access to medications and no indication that any patients were injured. |

– Police determined the man meant no harm and no further action was had.

– Hospital memos sent to: (1) remind staff to wear their hospital identification, (2) encourage staff to stop unfamiliar faces from going into unauthorized areas, and (3) Inform staff that security would take down the names of staff without hospital badges and would be asked for another photo identification. |

| Case #4: Canada and United States

Since 1991: 30-year history of impersonating nursing and non-healthcare professions. – Ottawa: (1) OriginElle fertility clinic health centre (2) Argyle Associates dental surgery clinic (3) Medical Clinic – Multiple cities in Ontario – Properties Medical Clinic, Calgary – Vancouver (1) 06/2020-06/2021: 1 year at BC Women’s Hospital. (2) Royal Arch Masonic Home – Surgical clinic, Victoria – Colorado Springs – Florida |

– Completed 2 of 4 years of nursing education in Colorado. She was never certified, but she posed as a nurse by providing the name of a real nurse and used at least 6 different aliases, and forged numerous documents, including: a resumé, registered nurse certificate, and fake provincial identity cards.

– Caught via suspicious colleagues (bedside manner, lack of professionalism, technical shortfalls, etc.) or facial recognition software that recognized issues with her forged IDs. – Forged prescriptions and performed injections and is suspected of administering sedatives and anesthetics, leading to: (1) a Vancouver patient suspecting that her pain wasn’t managed correctly during a hysteroscopy and endometriosis-related biopsy, (2) a patient suffering from pain and loss of movement in both hands for nearly 2 weeks due to multiple blood draw attempts, (3) An estimated 1000 women being impacted from B.C. Women’s Hospital, and (4) many patients under her care requiring therapy. |

– 67 adult convictions in 3 provinces and 2 states, including: criminal negligence causing bodily harm, assault with a weapon (brandishing a needle), and personation with intent.

– Served 3 jail sentences and was sentenced to 7 years in prison in 2022. – B.C. Women’s Hospital has done a hospital review to ensure there are no imposters in their system. |

| Case #5: United States

Beaumont Hospital, Michigan 1995-2010 15 years

|

– Attended medical school but did not graduate.

– Posed as s MD and PhD cardiologist and directed Beaumont’s medical simulation and research program. Used his experiences and skills as a certified commercial pilot to develop computer simulations and team-based medical training. – Caught by a routine background check. – Secured millions in research grants, including from the department of defense, and published 6 times in 5 journals. He gave numerous talks to other healthcare professionals at national medical organizations, including the American College of Cardiology. Didn’t treat patients nor had privileges at the hospital and much of his work focused on teamwork. |

– Resigned from his positions, has been grounded as a pilot, and some of his papers have been amended or retracted.

– Many colleagues valued his work, and the American Medical Association was going to have him continue to lead a seminar but would change his biography. However, this was cancelled after leadership at the American Medical Association found out. |

| Case #6: United States

UCLA Medical centre, California 01-06/1999 6 months |

– Posed as surgery resident via a lab coat, stethoscope, and stolen parking pass and key to the residents’ lounge.

– Discovered due to his unusual lab coat that had a picture of himself and him actively covering his identification badge. – The impersonator and UCLA claim no patients were treated. |

– 9 misdemeanor charges, including impersonating a doctor, forging prescriptions, and theft.

– Sentenced to 6 months of psychiatric counselling and 2 months in jail. |

| Case #7: United States

Florida: (1) 10/2015: Illegal medical practice (2) 01/2015: St Mary’s Medical Centre’s doctor for 1 month and (3) 02/2016: Illegal medical office |

– Claimed to have a PhD and certifications from several alternative medical organizations. Set-up a profile on a website that provides physician information.

– Did not treat patients at St. Mary’s, but was present during gynecological exams. |

Unknown |

| Case #8: United States

Several clinics, Los Angeles and Southern California 1976-2000 25 years |

– Attended but never graduated medical school and was a former pharmacist that lost his license. In 1989, he stole the identity of a pharmacist.

– Impersonated a doctor with the same name and obtained copies of his medical license and degree. In 1984, he tried applying for hospital privileges, but the doctor he was impersonating advised the authorities. – Performed minor surgeries and his misdiagnoses and improper medication prescriptions led to: (1) the death of a patient in 1980 after a missed adult-onset diabetes diagnosis and (2) several patients losing their jobs. Discovered by a colleague who observed his improper surgical technique and protocols and missed diagnoses. |

– Charged several times but continued practicing until 2000. |

| Case #9: United Kingdom

9 hospitals 2013-2015 2.5 years |

– Had previous medical training but was not certified to practice. Faked documents and impersonated a doctor.

– Caught when the human resources department realized that a smart card had already been issued to a doctor with the same name. – Treated more than 3,000 patients, but no evidence of harm. |

– 6-year jail sentence. |

| Case #10: United Kingdom

3 medical centres 04/2004-02/2011 7 years |

– Had previous medical training. Worked as a doctor and nurse by forging a degree and was discovered through his falsified CV which had prestigious claims, such as working for the United Nations.

– Did not appear to harm any patients. |

– 15-month jail sentence. |

| Case #11: Germany

2006-2011: Elderly care nurse 03/2016-06/2017: Assistant doctor at a hospital’s psychiatry ward for 15 months |

– Forged documents and was discovered in 2017 due to this forgery.

– Some claim that he was in a training phase and did not perform independent work, but others said that he often made mistakes and, due to staffing shortages, was sometimes in charge of a ward. |

– Was declared unfit to stand trial and case was dismissed due to the imposters’ psychosis and paranoid schizophrenia. |

| Case #12: Greece

Agios Andreas Hospital, Skyros 1993-2014 21 years |

– Submitted fake degrees, were viewed by Greek authorities and police, but their authenticity was never verified. The Greek Ministry of Health discovered this only after a citizen complaint and the mayor of Skyros receiving numerous complains about dangerous medical care on the island.

– Worked as a plastic surgeon and was head of Skyros hospital for 14 years, despite not being physically present in Skyros 5 months out of the year. |

– Received a life sentence. |

| Case #13: Australia

6 hospitals, 4 cities, New South Wales and pharmaceutical and clinical trials companies (Astra Zeneca and Novotech) 2003-2016 |

– Indian medical intern that stole the identity of a close friend and rheumatologist in India. He was able to register with the Australian medical board, despite never attending or passing examinations with the Australian College of Emergency Medicine. Lost the right to practice medicine in 2014 but was a registered member of the Australian Medical Association as recently as 2016.

– Inconsistencies in his application were not found due to staff shortages and time pressures. – Continued to work despite fraud allegations made by 2 senior doctors in 2006/7. Some reports state that these doctors were not taken seriously and threatened with reprimands for bullying the impersonator, who was described as above average in his performance reviews. – Harm seems to have been mitigated due to not having worked independently or not having patient contact at the pharmaceutical and clinical trials companies, but there was 1 identified incident of inadequate treatment for a broken arm and a patient complaint for not being given medication for her anxiety and heart condition. |

– Fined, institutions recouped the costs lost due to salary, and charges were laid, but he fled back to India.

– Australia’s health system now handles registration at the national level and New South Wales health requires direct verbal confirmation from all doctors. |

| Case #14: Australia

Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital and Ronald McDonald House, South Brisbane 05-12/2018 |

– Lost his job as an orderly but stole security credentials and pretended to be a surgeon.

– Caught when trying to renew his credentials with the security guard. – Wanted to make friends and never interacted with patients or tampered with medication. |

– Fined but was not convicted or sentenced to jail time as he did not attempt to treat patients and suffers from a mild intellectual impairment. |

| Case #15: Australia

2 states 1998-2009 12 Years |

– Former Serbian secret service registered as a psychologist via fake documentation and university credentials, including a 1995 master’s from the University of Belgrade from a program that was not offered until 2004.

– Discovered when trying to bill claims made while being overseas. – Performed over 7000 consultations and was paid more than $1 million by 2 government agencies. |

– Sentenced to 5 years and 2 months. |

|

Waikato hospital 2015 6 months |

– Impersonated a United States psychiatrist with a similar name and obtained original copies of degrees and forged other documentation by gathering information on the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology’s (ABPN) website. He provided 3 references, one of which was his brother who pretended to be a fellow doctor.

– Has a medical degree, but not in psychiatry and tried to work previously in New Zealand in 2012, but was refused due to a lack of qualifications. He attempted again in 2014 with the aforementioned fake documentation and succeeded. – Able to prescribe medication. |

– Sentenced to 4 years and 3 months in prison and has been deported to his native India and is not permitted to return to New Zealand. – ABPN has reviewed the information that can be gathered from its website. |

Figure 1: For both A and B: these illustrations are an approximate visual demonstration of the size and appearance of hospital identifications and the proportions of elements may not be exact. For simplicity, they are unilingual English.

The comments section is closed.

Made me think of an experience my mother had many years ago when she had to go downstairs to the lab to get her blood drawn after she saw the doctor. The women couldn’t get the blood samples from her arm so she proceeded to try from the vein on my mother’s hand. She said it was painful and have never had trouble before, and shook it off as a new technician.